What keeps people from participating? Understanding barriers to democratic engagement in Europe

Political participation forms the cornerstone of democratic governance, yet across Europe, large parts of the population remain on the margins of decision-making. This is not only a matter of individual choice; it reflects structural, cultural, and institutional barriers that systematically exclude certain groups. Understanding these barriers is essential for initiatives such as MultiPoD, which aims to create multilingual and multicultural spaces where all citizens can take part in shaping Europe’s political future.

The foundation: Why people don’t participate

Brady, Verba, and Schlozman (1995) offer a simple yet powerful framework to explain non-participation: people stay away from politics “because they can’t, because they don’t want to, or because nobody asked” (p. 271). These correspond to three key theories. First, the socio-economic status (SES) model holds that higher education, income, and occupational stability give people the resources and confidence -time, money, social networks- to vote, volunteer, or campaign. Second, the civic voluntarism model emphasises motivation and opportunity. Even with resources, individuals need interest, skills, and invitations from recruiting agents, such as political parties, community groups, or NGOs, to get involved. Third, the rational choice approach views participation as a cost-benefit decision: when the perceived effort outweighs the expected impact, people opt to “free-ride” and leave action to others.

In Europe, studies confirm the weight of SES: regions with higher average income and education see greater turnout, volunteering, and political discussion (Gallego, 2007). But resources alone do not tell the whole story. Feelings of political efficacy -believing one’s voice matters- and trust in institutions are equally decisive, as are available channels for mobilisation (Hooghe & Marien, 2013).

Barriers for linguistic and ethnic minorities

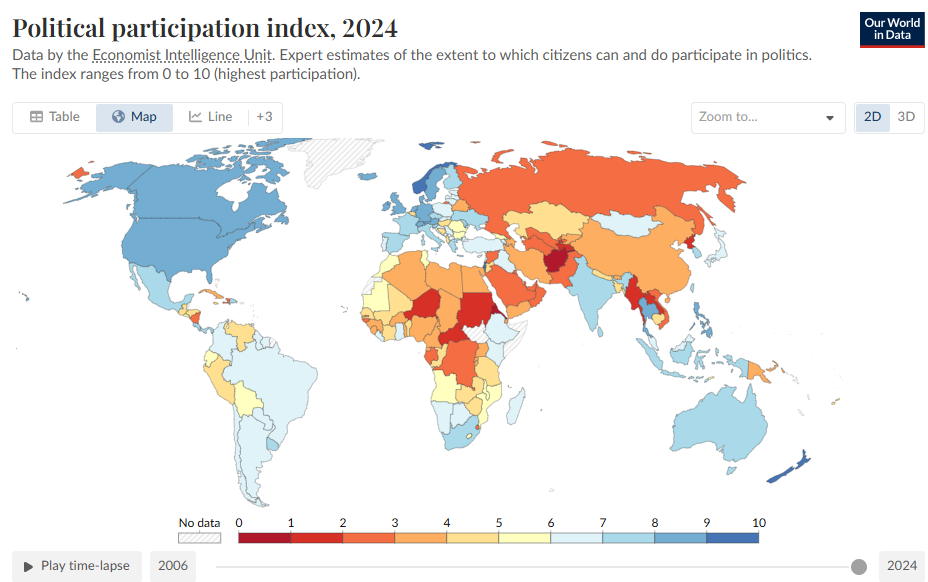

For Europe’s linguistic and ethnic minorities, the barriers are even higher. The 2024 Political Participation Policy Index reveals that political participation is consistently the weakest area of integration policy across EU member states, with particularly stark gaps affecting New Europeans -naturalised migrants, second-generation citizens with migration backgrounds, EU mobile citizens, and third-country nationals (Yavçan et al., 2024). Only 14 EU countries grant third-country nationals voting rights at the municipal level, while the remaining 13 exclude them entirely (Long, 2025). Moreover, access to information in minority languages remains limited in many member states, affecting citizens’ ability to understand policies, follow electoral debates, or exercise their voting rights effectively (van der Velden, 2018). Linguistic exclusion is not a minor issue: research shows that immigrant-origin populations across Europe participate in elections at significantly lower rates than native-born citizens, even when controlling for education and income (Bird et al., 2011).

Structural discrimination adds further hurdles. Common barriers include manual registration processes with tight deadlines, limited outreach campaigns, and a complete absence of intersectional approaches that address the specific needs of migrant women, LGBTIQ+ migrants, or migrants with disabilities. Political parties -the key gatekeepers to political office- tend to draw candidates from majority-dominated networks, sidelining minority voices (Bird et al., 2011). The result is stark underrepresentation: across Western Europe, minority groups often make up sizeable portions of the population yet remain absent from parliaments or over-concentrated in local-level politics with limited influence.

The role of non-institutional participation

Faced with such barriers, many groups find alternative ways to engage politically outside formal institutions. Non-institutional participation, such as demonstrations, petitions, consumer boycotts, and online activism, has grown significantly in recent decades, especially among youth and minority communities (Norris, 2002; Theocharis & van Deth, 2018).

Research in Europe shows that while immigrant-origin youth may vote less than their peers, they are more likely to engage in protests or digital activism to make their voices heard (Mentesoglu Tardivo, 2025). Similarly, women’s rights movements across Europe have leveraged non-electoral channels, including marches, social media campaigns, and grassroots networks to win policy changes when formal institutions were unresponsive. These “new grammars of action” do not signal disengagement but rather reflect adaptive strategies by groups historically excluded from power.

Implications for European democracy

The persistence of participation gaps undermines the inclusiveness and legitimacy of European democracy. When certain groups -whether defined by language, ethnicity, gender, or socio-economic status- are consistently underrepresented, policy outcomes risk reflecting the interests of the few rather than the many.

MultiPoD addresses these challenges by combining technology and behavioural insights. Its multilingual, culture-specific language models and visual analytics tools lower communication barriers, reaching people in their own languages and contexts. Equally important is valuing non-institutional forms of engagement, which reveal the many ways citizens seek to influence public affairs. By embracing both traditional and new avenues of participation, MultiPoD can help build a more resilient, inclusive democratic future for Europe.